The Impact of Film Properties on Corrosion Resistance

in Waterborne Acrylics and Next-Generation Low-VOC Resin Development

Corrosion protection of organic coatings has received a significant amount of study in both academia and industry. Without considering anticorrosive pigments or other corrosion-inhibiting additives, three of the most commonly highlighted factors influencing corrosion resistance are barrier properties (water and O2 permeability), adhesion and electrochemical impedance. When attempting to identify the rate-limiting or primary protection mechanism, the various literature studies often conflict. Discrepancies may arise for a number of reasons, including differences in polymer chemistries, test methods and conditions. To explore the disagreements, a focused study of 21 styrenated acrylic resins in clear formulations was conducted in an effort to correlate film properties with corrosion resistance on flat, bare, cold rolled steel. The study was then extended into high-gloss pigmented systems. The structure property relationships derived from this work were then applied to the development of next-generation, low-volatile organic compound (VOC), direct-to-metal (DTM) polymers.

Introduction

Historically, 1K waterborne styrenated acrylic resins have been utilized in the light-duty industrial maintenance sector, often sold for DTM coatings. DTM in this context refers to the direct application of a single coat (or optionally multicoat) paint to a metal substrate without a primer to provide adhesion and corrosion resistance. Thus, the DTM coating must provide the full balance of properties expected of a metal protective system including, among others, corrosion resistance, adhesion, chemical resistance, UV resistance and hardness. This presents significant challenges in polymer design, forcing the chemist to balance what often appear to be competing properties. When considering ASTM B117 as the accelerated corrosion testing method, performance ranges for commercially available 1K DTMs based on styrenated acrylics are typically between 24-300 hrs exposure in a single coat at ~ 2 mil dry film thickness (DFT). Some more specialized styrenated acrylic DTMs can achieve > 500 hrs.

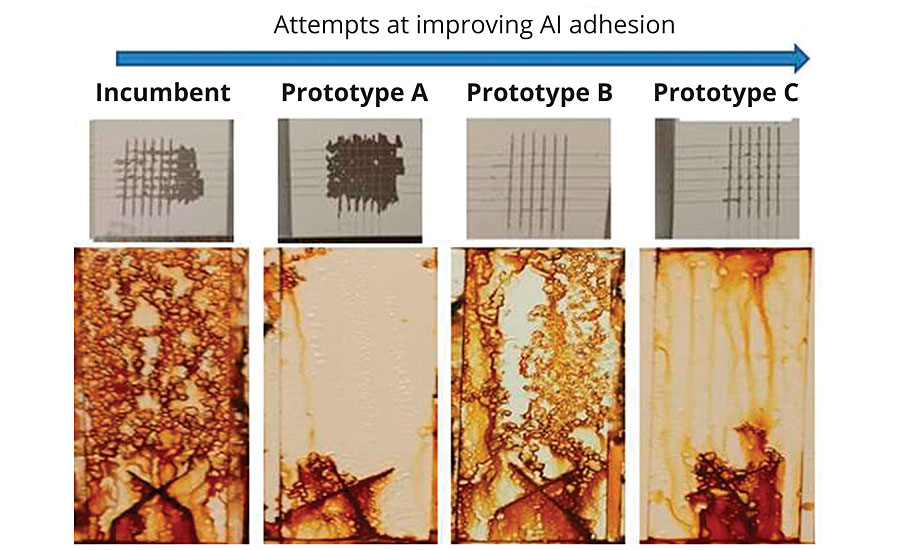

One of the major driving forces for new development in this space is VOC reduction. Legacy DTM products tend to be formulated to < 250 g/L, but a combination of regulation, consumer pull-through and voluntary adoption by suppliers has driven a demand for high performance under 100 g/L and lower. In a recent development project for a < 100 g/L VOC-capable styrenated acrylic DTM, significant difficulties arose in maintaining corrosion resistance while trying to improve adhesion to aluminum substrates. Working off the platform of an in-house incumbent polymer, the initial project focus was to improve its corrosion resistance as measured by ASTM B117 salt fog on flat, untreated cold rolled steel (CRS). Early prototypes accomplished this, but yielded reduced adhesion to aluminum (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 » Aluminum crosshatch adhesion vs. corrosion resistance on CRS (2 mil DFT, 400 hrs B117) of incumbent resin vs. Prototype A.

In developing prototype A, the compositional changes necessary to deliver the improved corrosion resistance limited its ability to adhere to aluminum. Another round of prototype synthesis was conducted to improve the aluminum adhesion. Results were mixed, with a general trend emerging of improved adhesion at the expense of corrosion resistance. A representative subset of the evaluated prototypes is summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2 » Prototype resins with aluminum adhesion vs. corrosion resistance on CRS (2 mil DFT, 400 hrs B117).

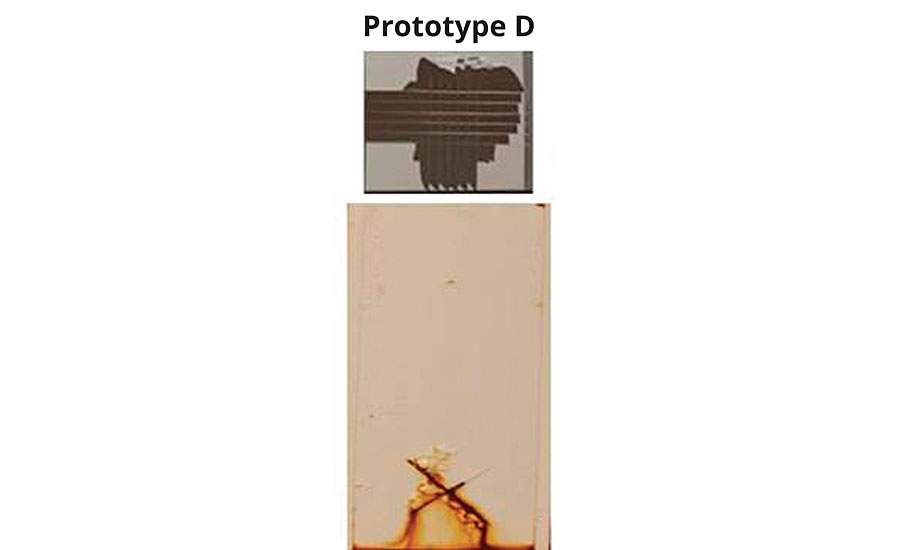

In light of these findings, an additional prototype (Prototype D) was synthesized, specifically deemphasizing aluminum adhesion as a property (Figure 3). Prototype D produced a 0b crosshatch adhesion result, but yielded the best corrosion resistance seen to that point. The results prompted an in-depth review of corrosion and adhesion mechanisms in an attempt to explain the apparent inverse relationship between the two properties.

FIGURE 3 » Aluminum adhesion vs. corrosion resistance on CRS (2 mil DFT, 400 hrs B117) of Prototype D.

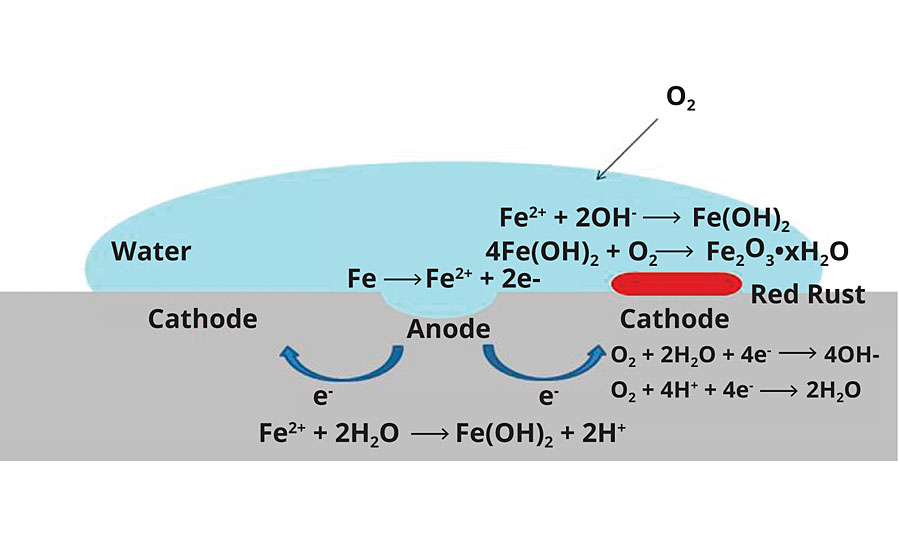

Steel Corrosion and Mechanisms of Protection

A simplified schematic of steel corrosion is presented in Figure 4. For corrosion to initiate and propagate, certain conditions are required: 1) an anode; 2) a cathode; 3) oxygen (or other reducible species, e.g. CO2); 4) water (for ion flow); and 5) electrolytes (e.g. NaCl, accelerate corrosion processes). For steel, there is an additional requirement of a pH < ~ 9.5. A thin passivation layer of oxide forms above this pH, shutting down further corrosion. Elimination of any one of these components can inhibit the corrosion process. For corrosion prevention with organic coatings, without considering anticorrosive pigments or small-molecule corrosion inhibitors, there are several potential inhibition mechanisms:

FIGURE 4 » Simplified schematic of corrosion on steel.

- Prevention of water and/or oxygen from penetrating the coating film – these mechanisms will be collectively referred to as barrier properties.

- (a)Exclusion of water from the surface or prevention of anode/cathode formation via strong coating wet adhesion properties.

(b)Passivation of either the anode or cathode as it forms via the adhesion properties of the coating. - Inhibition of electrolyte flow via film resistance – generally measured via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS).

Literature Review

Attempts at elucidating the role organic coatings play in preventing corrosion stretch back decades. There has been significant disagreement over the primary mechanism by which coatings inhibit corrosion, with examples of studies concluding that any one of the three components – barrier properties, adhesion properties or impedance – is the limiting factor. Historically, barrier properties were thought to be of primary importance. One of the earliest challengers to this was Mayne and coworkers.1-3 Mayne performed extensive work beginning in the late 1940s on the mechanisms of corrosion protection in coatings. The common theme that arose from this work was that the rate of permeation of the elements necessary for corrosion to occur (i.e. water and oxygen) was anywhere from one to several orders of magnitude too high, depending on the chemistry, for barrier properties to be a limiting factor in corrosion control. Instead, Mayne argued that the coating provided a high resistive barrier to electrolyte flow, inhibiting the formation of a complete galvanic cell.3 This was confirmed via EIS measurements, which appeared to correlate well with accelerated corrosion testing on steel immersed in salt water.

Similar results were observed independently in 1948 by Bacon and coworkers who completed an extensive EIS study of 300 coatings systems of different chemistries and arrived at the general rule of thumb that maintaining an impedance of >106Ω was required for good corrosion resistance.4 Other researchers disagreed with the barrier property findings of Mayne and others, producing research that suggested oxygen transport through the coating was the rate-limiting factor in corrosion resistance.5-7 A more sophisticated model was proposed by Funke that posited that a combination of oxygen transport inhibition and loss of adhesion via water incursion drove corrosion.8

Additional researchers concluded that adhesion under saturated conditions, or wet adhesion (as opposed to dry adhesion), either alone or in concert with barrier properties, was of primary importance in inhibiting corrosion.5,9 The combined efforts of these works and many others proved that both corrosion and its control by organic coatings were extremely complex and difficult to model processes. More recent works have tended to favor EIS as the standard predictive tool.10-13 An in-depth review and theoretical treatment of EIS as a technique applied to coatings is provided by van Westing.14 Despite this, adhesion and barrier properties continue to be a significant component of the corrosion conversation.

Several potential issues arise when attempting to compare the various models of corrosion resistance generated by different researchers. The cited studies and other works in this area are not necessarily consistent with one another in their resin chemistry, formulation, metal type, surface prep, accelerated corrosion method, analytical techniques, etc. This can make attempting to develop a unifying theory of corrosion protection via organic coatings difficult. As a resin supplier, we are primarily concerned with the development and study of waterborne, styrenated acrylic resins. As relatively polar 1K systems, styrenated acrylics are likely to exhibit significantly different behavior in, say, barrier properties vs. highly crosslinked epoxies, chlorinated rubbers or semicrystalline polyolefins. To develop styrenated acrylics with optimal corrosion resistance while retaining the necessary balance of other properties, a more focused study is required to isolate the structure/property relationships for a single chemistry.

To better make comparisons between experiments and draw conclusions specific to a single chemistry, the work presented here will focus on corrosion resistance of waterborne, styrenated acrylics as measured by ASTM B117 salt fog on flat, untreated CRS. Specifically, the CRS panels tested were R-series Q-panels, which were received clean and with no further surface prep prior to coating.

Experimental Observations

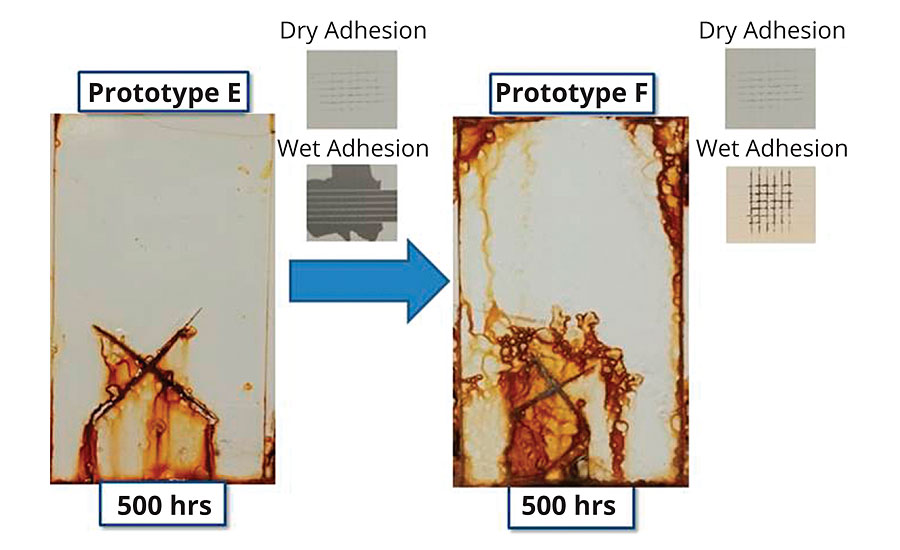

The results from Figure 2 indicate that seeking to optimize adhesion properties can be detrimental to corrosion resistance. Figure 5 illustrates an example in which a prototype with good dry adhesion but poor wet adhesion to CRS was adjusted compositionally to impart wet adhesion via an increase in acid monomer content. Wet adhesion was tested by applying a 10-mil wet drawdown, curing at ambient conditions for 7 days, forming a 3-mm crosshatch and exposing to a wet paper towel for 30 min. After 30 min, the paper towel was removed, the film patted dry and the crosshatch immediately tested with adhesion tape.

FIGURE 5 » Effect of wet adhesion on corrosion resistance (2-2.2 mil DFT, B117).

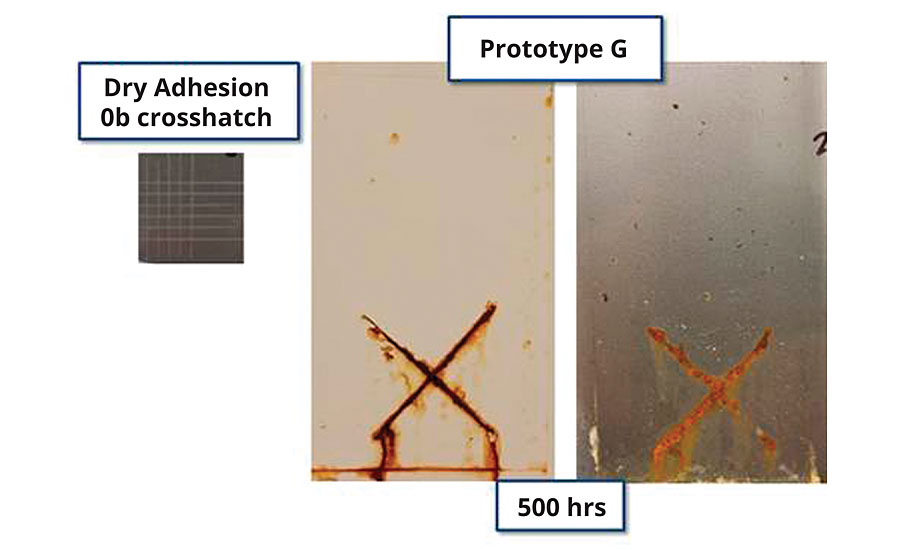

An additional prototype was then made reducing the adhesion properties of Prototype E via acid monomer reduction such that the resin failed dry crosshatch adhesion on CRS. The observed corrosion resistance (Figure 6), presented both in a pigmented high-gloss formulation (2 mil DFT) and a clear formulation (1 mil DFT), exhibited an incremental improvement in corrosion resistance over Prototype E. Even with poor dry and wet adhesion, scribe propagation was unexpectedly minimal (< 3mm), and field corrosion was isolated to a few pin points.

FIGURE 6 » Corrosion resistance (2 mil DFT for white, 1 mil for clear, 500 hrs B117) of prototype with poor dry adhesion on CRS.

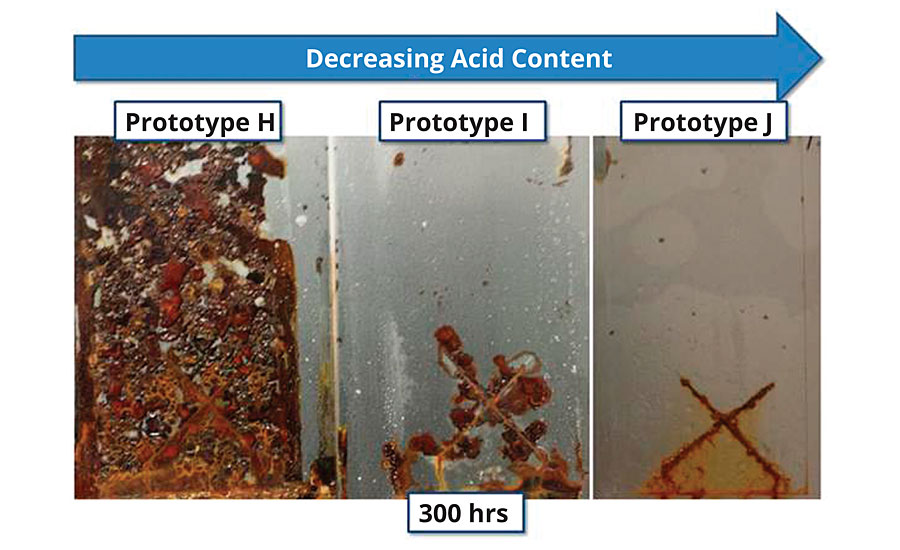

Insight as to the underlying mechanism and interplay between these properties may lie in work performed by Ulfvarson and Khullar, in which they demonstrated an inverse correlation between the ion exchange capacity of the resin and its corrosion resistance.15 Framed another way, increasing the acid monomer content of a resin is expected to be detrimental to corrosion resistance. For waterborne styrenated acrylics, this presents an interesting challenge, as these polymers rely on acid groups both for metal adhesion and colloidal stability. To test this, a series of resins was synthesized, changing nothing but the acid monomer level. Each resin was tested for corrosion resistance in a clear formulation (Figure 7). A significant correlation between acid level and corrosion resistance emerged, with lower acid levels yielding superior corrosion resistance.

FIGURE 7 » Corrosion resistance (1.5 mil DFT, 300 hrs B117) of three prototypes with decreasing acid monomer levels.

Clear films provide easily observable visual cues, particularly in the cases of field corrosion and water incursion. In the Prototype J (Figure 7), water has visibly penetrated the film and is present at the film/substrate interface on > 70% of the surface area. Yet, in the vast majority of the field area, no visible corrosion is present, and corrosion protection continues even after water has penetrated to the substrate surface. This indicates that water incursion, in and of itself, is not the rate-limiting step in the initiation and propagation of corrosion at the steel surface. Additionally, polymers that pass the standard wet adhesion test quickly lose adhesion strength in the salt fog cabinet. This is consistent with the work of Walker.16 Resins that pass wet adhesion as measured by one-hour immersion in water fail crosshatch adhesion upon removal from the salt fog cabinet. Adhesion strength is typically low enough after 300 hrs exposure to salt fog that the entire film could be lifted from the substrate with minimal effort (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8 » Loss of adhesion after 300 hrs exposure to the B117 salt fog cabinet.

Also, despite the loss of substrate adhesion, it is apparent from Figure 8 that no significant scribe propagation or field rust had occurred.

Systematic Study of Styrenated Acrylics

Experimental

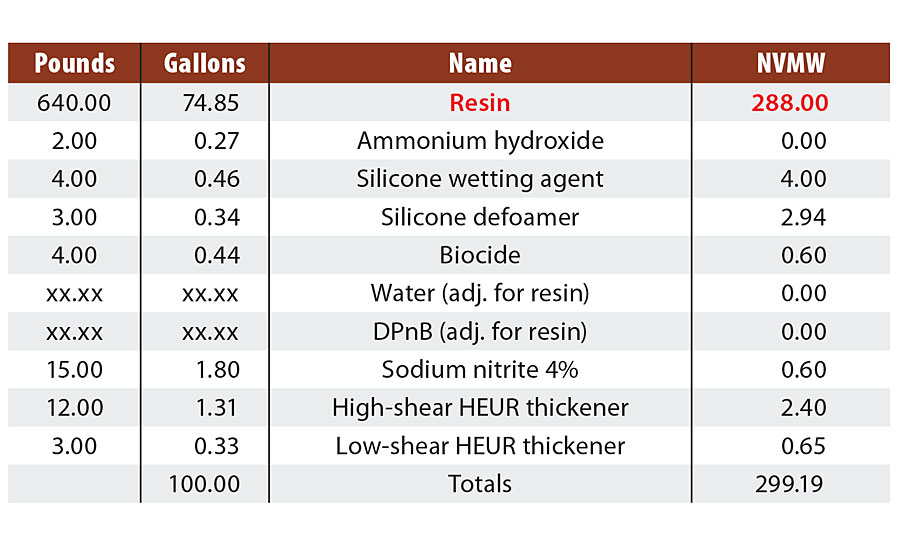

In an effort to understand both the findings from literature and experimental observations, and begin to pursue a more unified theory of corrosion protection specifically for styrenated acrylics, a study evaluating 21 commercially available styrenated acrylics (henceforth referred to as Resin A through Resin U) was conducted. The resins were formulated into identical clear formulations, only adjusting coalescing solvent level based on the minimum film formation temperature of each resin (Table 1). Select film properties were then evaluated for correlation with accelerated corrosion in a B117 salt fog cabinet (Q-FOG, Q-lab) at a target of 3-3.5 mil DFT in a single coat on flat, untreated CRS (4”x6” R-series Q panels) via drawdown. Results discussed here will focus on adhesion, impedance, film hardness, water vapor transmission and oxygen transmission. Future papers will extend the structure/property model to other performance tests such as Cleveland humidity and cyclic prohesion.

TABLE 1 » Start point clear formulation for film property testing.

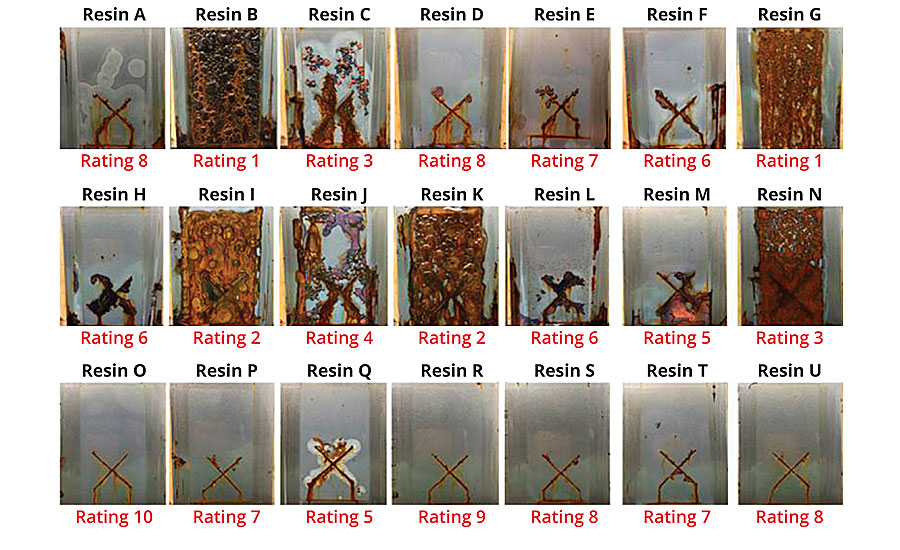

Each of the resins was exposed in B117 salt fog and monitored for progression of corrosion at 66 hrs, 240 hrs and 560 hrs (560 hrs panels in Figure 9). To analyze the data, the panels were force ranked on a discrete 10-unit scale, with 10 being the best ranked panel and 1 being the worst.

FIGURE 9 » Corrosion results (560 hrs B117) and ratings of Resin A through U (3-3.5 mil DFT, CRS).

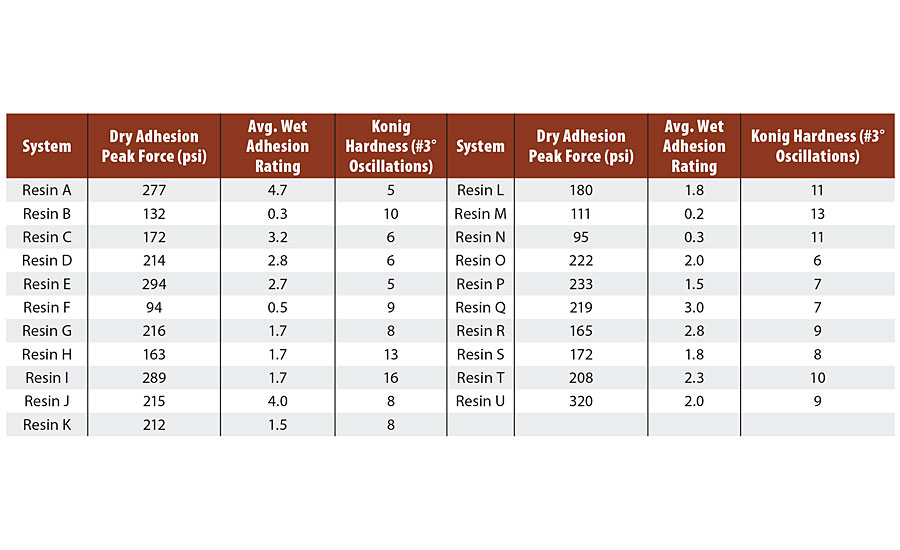

For dry pull off adhesion, coatings were applied over 4”x6” R-series Q panels at 10 mil wet DFT and cured at ambient conditions for 7 days. Metal dollies were fixed to the film via an epoxy adhesive for 24 hrs. The test area was separated from the rest of the film by cutting around the dolly and the peak force (psi) necessary to remove the film from the substrate was measured (Table 2).

TABLE 2 » Pull-off adhesion on CRS (R-series Q panel), average wet adhesion rating, and Konig hardness for Resin A through U.

In an effort to quantify the wet adhesion properties of the films, a series of immersion tests was run with a ladder of exposure times. Coatings were applied over 4”x6” R-series Q panels at 10 mil wet DFT and cured at ambient conditions for 7 days. The initial test was the 30-min wet paper towel test described before. The crosshatches were rated on a scale of 0b-5b, with 0b meaning > 65% film removal and 5b meaning 0% film removal. Resins that retained ≥ 2b adhesion in this test were then immersed in water for 1 hr and retested for adhesion. Additional immersion times were 24 hrs, 48 hrs, 4 days and 1 week. At each time point, resins that exhibited ≥ 2b adhesion were carried through to the next immersion time point. An average of the six runs was taken with results summarized in Table 2.

Barrier properties are known to be directly related to polymer Tg, which is in turn directly related to measured film hardness. Coatings were applied over 4” x 6” glass panels at 10 mil wet DFT and cured at ambient conditions for 7 days. Konig hardness was measured via oscillations at 3⁰ on a pendulum hardness tester from BYK (Table 2).

For water vapor and oxygen transmission, each coating was drawn down on a silicone release liner at 15 mil WFT and cured at RT for 7 days. Three 4-cm-diameter disks were cut from each film. Samples were measured for water vapor transmission on an Illinois Instruments 7002 WVT for 24 hrs at 90% humidity, 100 ⁰F.

For EIS, samples were prepared in an equivalent manner to those prepared for B117 salt fog. EIS was conducted on the films upon initial immersion in a 5% NaCl solution and after 24 hrs of immersion. Impedance values at low frequency (0.01Hz, via potentiostat) at 24 hrs immersion were used for correlation assessment.

Results and Discussion

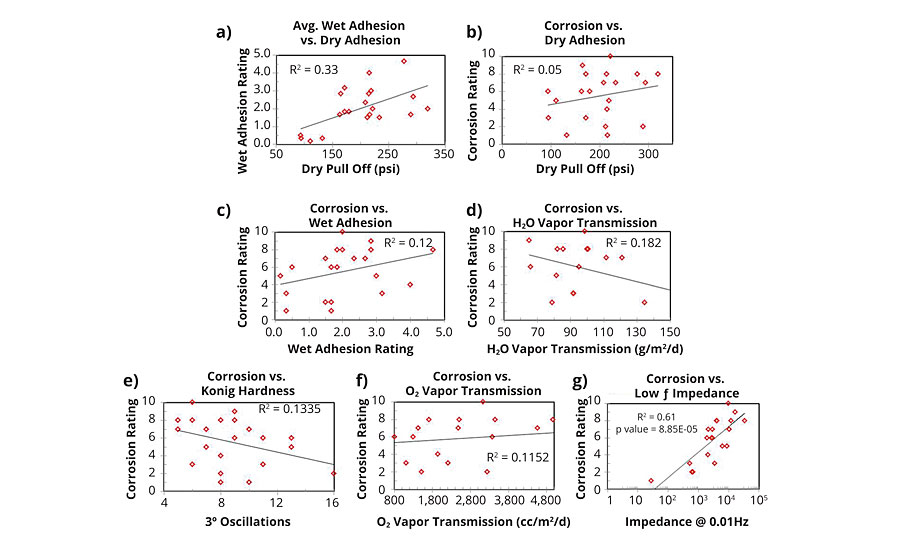

A series of plots (Figure 10) was generated to investigate any correlations that might arise amongst the following pairs: dry adhesion/wet adhesion; dry adhesion/corrosion resistance; wet adhesion/corrosion resistance; water vapor transmission/corrosion resistance; Konig hardness/corrosion resistance; and 24-hr low-frequency impedance/corrosion resistance.

FIGURE 10 » Correlation of physical properties: a) dry pull off adhesion vs. avg. wet adhesion; b) corrosion resistance vs. dry pull off adhesion; c) corrosion resistance vs. avg. wet adhesion; d) corrosion vs. H2O vapor transmission; e) corrosion vs. Konig hardness; f) corrosion vs. oxygen .

Dry and wet adhesions were moderately correlated, with initial strength of dry adhesion explaining a small portion of the wet adhesion data. Neither dry nor wet adhesion showed a significant correlation with corrosion resistance. Prior to this study, based on experimental observations, the hypothesis was that a negative correlation between adhesion and corrosion resistance would emerge, but this was not the case. Similarly, water vapor transmission, oxygen transmission and Konig hardness did not exhibit strong correlations with corrosion resistance. Future work will compare water vapor transmission with liquid water uptake data and any respective correlation with corrosion resistance. The two physical forms of water represent two different aspects of barrier properties, as water vapor transmission is dominated by bulk diffusion while liquid water transport proceeds primarily via capillary action.

Low-frequency impedance correlated strongly with the observed corrosion resistance, with impedance explaining a majority of the experimental data (R2 = 0.61). The remaining variability may arise in film properties still to be measured and may also be inherent to the test due to panel to panel inconsistencies in film quality. Data correlation may also change/be improved by extending the EIS exposure time to one week. However, one week, or 168 hrs, is approaching a meaningful timescale to be able to observe differences in B117 corrosion performance of styrenated acrylic resins, thus reducing its effectiveness as a quick screening tool.

Based on these findings, film impedance is an important part of the model of coating corrosion resistance. However, a significant portion of the data remains unexplained. An important takeaway from the adhesion results is that, contrary to previous experimental observations, achieving good wet adhesion properties is not necessarily detrimental to corrosion resistance. Good adhesion is also not strictly necessary to achieve good corrosion resistance. In real-world applications, however, good adhesion properties serve another important purpose in reducing the likelihood of coating film damage and substrate exposure. Polymers with good wet adhesion are more likely to resist delamination/removal from the substrate from mechanical damage when hydrated due to rain or high humidity. Any damaged area without coating coverage is readily susceptible to corrosion processes.

Next-Generation Development and Conclusion

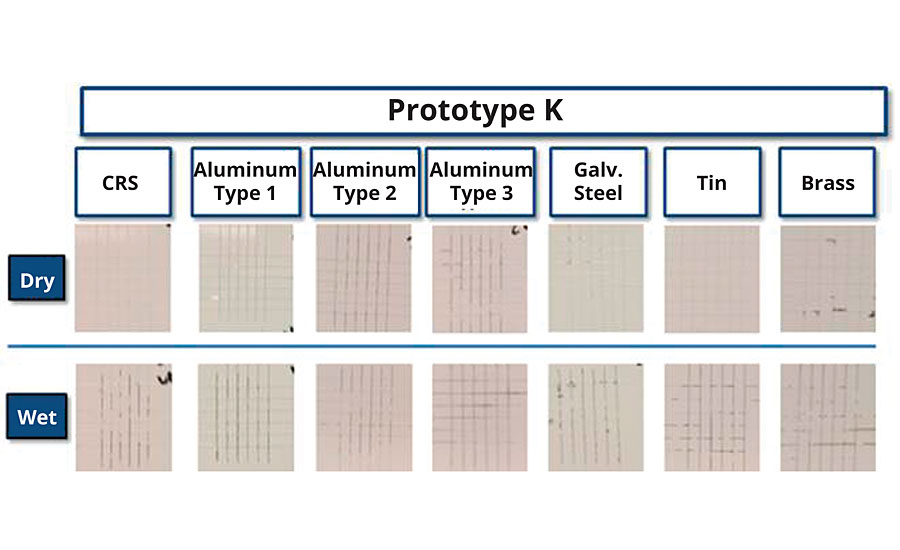

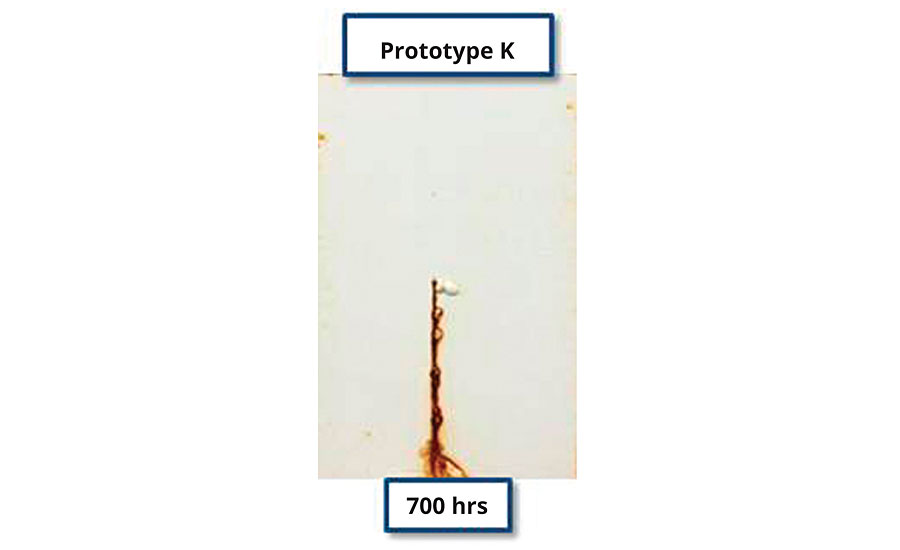

The adhesion/corrosion balance of the previous study yielded significant new insights into resin design. Polymers with good wet adhesion and good corrosion resistance could be isolated, and those properties correlated back to their monomer compositions and particle morphologies. The knowledge gained drove development of a next-generation, low-VOC (< 50 g/L) styrenated acrylic DTM resin with high-performing adhesion and corrosion properties. A new prototype was synthesized that provided a robust adhesion profile across many substrates, capable of passing dry and wet adhesion within 72 hrs of application (Figure 11). Additionally, the corrosion resistance (Figure 12) surpassed that of most previously evaluated prototypes while delivering a comprehensive wet and dry adhesion profile. The novel synthetic approaches demonstrated here achieved improved adhesion without negatively impacting the film’s impedance or relying on high levels of acidic functional groups.

FIGURE 11 » 24-hr wet and dry crosshatch adhesion of Prototype H across a variety of metal substrates.

FIGURE 12 » Corrosion resistance (700 hrs B117, 2 mil DFT, CRS) of Prototype K.

Current efforts are focused on further optimizing the performance of Prototype K and continuing to drive down the VOC demand of waterborne styrenated acrylic DTMs. Additional unmet needs in this space such as adhesion to poorly prepared substrates (e.g. oily/greasy, dirty, rusted, etc.) are also being explored, leveraging learnings from the study presented here.

This paper was originally presented at the 2017 Waterborne Symposium in New Orleans. For more information, email allen.bulick@eps-materials.com.

References

1 Mayne, J. JOCCA, vol. 32, no. 352, p. 481-487, 1949.

2 Mayne, J. JOCCA, vol. 40, p. 183, 1957.

3 Mayne, J. The Mechanism of the Protective Action of Paints, Corrosion, Newnes-Butterworths, 1976, p. 15:24-15:37.

4 Bacon, C.; Smith, J.; a. R. FM. Ind Eng Chem, vol. 40, no. 1, p. 161-168, 1948.

5 Funke, W.; Haagen, H. Ind Eng Chem Prod Res Dev, vol. 17, p. 50, 1978.

6 Guruviah, S. JOCCA, vol. 53, p. 660, 1970.

7 Kresse, P. Pigment Resin Tech, vol. 2, no. 11, p. 21, 1973.

8 Funke, W. JOCCA, vol. 62, p. 63, 1979.

9 Parker, E.; Gerhart, H. Ind Eng Chem, vol. 59, no. 8, p. 53, 1967.

10 Bierwagen, G.; Tallman, D.; e. al. Prog in Org Ctgs, vol. 46, no. 2, p. 149-158, 2003.

11 Floyd, F.; e. al. Prog in Org Ctgs, vol. 66, no. 1, p. 8-34, 2009.

12 O'Donoghue, M.; e. al. Coatings & Linings, pp. 36-41, September 2003.

13 Shreeptahi, S.; Guin, A.; e. al. J Coat Tech & Res, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 191-200, 2011.

14 van Westing, E. Determination of Coating Performance with Impedance Measurements, Delft, 1992.

15 Ulfvarson, U.; Khullar, M. JOCCA, vol. 54, p. 604, 1971.

16 Walker, P. Off Dig Fed Soc Paint Technol, vol. 37, p. 1561, 1965.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!